It’s not us, it’s you: China’s surging overcapacities and distortive exports are pressuring many developing countries too

No. 3, November 2024

By Claus Soong and Jacob Gunter

The EU’s October 2024 tariffs on imported China-made electric vehicles (EVs) raised a debate in Europe about the level of market distortions coming from China’s exports, as well as fears about how Beijing might respond. Around the same time, Canada and the United States also opted for higher levies on Chinese EVs, and Washington imposed tariffs on several other goods too. So far, the discussion about managing market distortions from China’s exports has focused on these responses by wealthy G7 countries. Yet middle income and developing countries are also dealing with China’s surging exports, though their responses have received far less attention.

This edition of the Global China Competition Tracker aims to bridge that gap by tracking measures taken by some of the “G50” – the world’s 50 largest economies – and Beijing’s response.

It contains an overview of Beijing’s response patterns, and case studies of eight countries: Four Southeast Asian countries (Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia) which have been grouped into a regional comparison, as well as Mexico, Turkey, Brazil, and South Africa.

The trade protection measures taken by “G50” countries include:

- Raising high barriers to a range of imports from China, something Mexico has done to cement its US economic ties keeping the door open for Chinese greenfield investment

- Leveraging tariffs to attract greenfield investment, as Turkey did with EV tariffs

- Mitigating distortions impacting lower-end production or commodities, as Indonesia did to protect their local industry, while leaving untouched higher-value goods that Indonesia does not yet produce

- Managing distortions across a wider range of basic and advanced industries, as Brazil has done with steel to EVs, while avoiding risks to its own commodity exports to China

- Protecting domestic retailers from China’s ecommerce giants with measures covering small scale imports, as has been done by South Africa, Vietnam, Thailand, and Brazil

- Doing little or nothing and instead embracing the cheap goods that China’s overcapacities and subsidies bring to their economy, as many have done, including developed liberal economies like Australia or New Zealand and developing countries like Bangladesh or Tanzania

The wide range of measures taken by countries with their own unique mix of economic and political interests towards China shows the growing international concern caused by China’s economic model, subsidies, overcapacity, and surging exports. It also demonstrates key trends of how China does and doesn’t defend its economic interests with different countries – most notably, that Beijing seems willing to incur economic losses from trade defense measures when it believes it still has considerable potential for political wins, but will fight more intensely against economic losses when convinced a country is politically lost to them.

Mapping out the global response to China’s export surge

The “G50” are mapped out below, highlighting those that have taken recent measures on China’s exports to show the types of goods targeted. The product types vary significantly, take for example ‘elephant-print trousers’ (Thailand) and brass keys (Brazil) to semiconductors and ship-to-shore cranes for the US. We have categorized products into four main groupings:

- Commodities like steel, basic chemicals, and grain

- Basic manufactured goods like textiles and shoes, ball bearings, and basic hardware

- Advanced manufactured goods like diesel engines, automobiles, and solar panels

- E-commerce, like individually-ordered consumer products from companies like Shein, Temu, and AliExpress

Mapping out the global response to China’s export surge

The “G50” are mapped out below, highlighting those that have taken recent measures on China’s exports to show the types of goods targeted. The product types vary significantly, take for example ‘elephant-print trousers’ (Thailand) and brass keys (Brazil) to semiconductors and ship-to-shore cranes for the US. We have categorized products into four main groupings:

- Commodities like steel, basic chemicals, and grain

- Basic manufactured goods like textiles and shoes, ball bearings, and basic hardware

- Advanced manufactured goods like diesel engines, automobiles, and solar panels

- E-commerce, like individually-ordered consumer products from companies like Shein, Temu, and AliExpress

Beijing responds far more mildly to trade measures from developing countries

Many economies outside the G7 and friends face economic distortions from China’s growing exports and overcapacities, yet Beijing has often refrained from pushing back against their trade defense instruments. Based on trends identified in the map above and eight case studies (Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Mexico, Turkey, Brazil, and South Africa) presented below, China’s responses have been far less vigorous than when confronting similar measures from developed liberal market economies. Any retaliation has frequently been limited, narrow, and through the WTO. In a stark contrast, Beijing has faced off against the EU, United States, and like-minded countries (like Canada and Australia) with tit-for-tat measures and WTO cases at best, or blatant economic coercion at worst.

Beijing’s lack of retaliation to trade measures from “G50” middle-income and developing countries that hinder its economic interests suggest the following priorities and patterns:

- Beijing often puts a higher priority on geopolitics and the international recognition flowing from the bilateral relationship, so is willing to disregard trade defense measures on some steel, some manufactures, and some e-commerce by not retaliating. China prefers to maintain its political gains.

- Beijing may place more value on exports of critical goods to China (like agricultural, mineral, and energy commodities) than on maximum export sales in these markets, especially as it diversifies away from traditional commodity suppliers like the United States, Canada, and Australia.

- President Xi Jinping’s efforts to position China as the leader of the global south is a further reason for a softer response to developing countries’ measures against China’s exports.

- However, Beijing may prefer to defend its economic interests where there is little potential to sway countries away from US alignment. It may have written off many countries it believes are heavily aligned with the United States, such as NATO members and America’s Pacific Rim allies.

European policymakers can act on these findings, both autonomously, bilaterally, and through coalitions

First, European leaders should recognize the fact that they are far from isolated in acting on the spillovers of China’s economic model and overcapacity – a wide range of countries are identifying the same problems and taking action.

Second, as more countries impose such measures, it creates a collective legitimacy for measures already taken, in the pipeline, or being considered. This is helpful as countries tend to fear being the first mover on an issue; this nervousness was evident even among EU members debating Beijing’s likely response to the bloc’s EV tariffs. However, the EU can proceed more confidently with trade measures knowing many more countries are responding to China’s export surges. Equally, developing countries can act in the knowledge they are not the first to stick their heads out.

Third, the risks and opportunities for European companies engaged in third market competition will vary with each country. Governments are most likely to protect their country’s key economic interests and to accept the ‘benign distortions’ that threaten no material harm due to the lack of local competition. However, that dynamic creates a significant issue for those engaged in third market competition with China. Indonesia may be happy to import heavily subsidized EVs from China, but European carmakers will struggle with distorted competition in Indonesia’s market. Similarly, basic manufactured goods like textiles and footwear from rising economies like Indonesia must compete with Chinese exports in markets like the EU that are unlikely to unilaterally raise barriers on such products.

Coordination to get countries to act on such cases would likely be quite difficult to manage, but the effort could unlock significant benefits for both sides. As an example, Europe would lose out on imported clothing from China and Indonesia would lose out on imported cars from China if both raised barriers. But European automakers would benefit from fairer competition against Chinese automotive exports to Indonesia, just as Indonesia would benefit from fairer competition against Chinese clothing exports to Europe.

Case studies

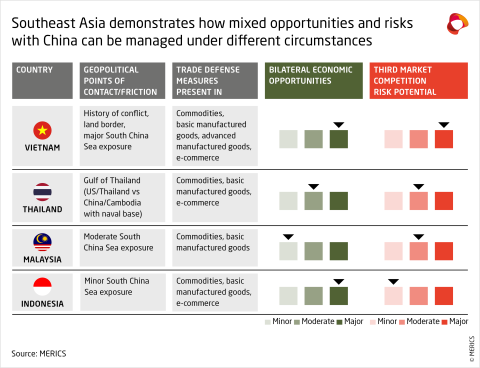

Below we examine trade measures already taken by a regional comparison of countries in Southeast Asia with Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia, each of which has varied economic and geopolitical relations with China, as well as four other countries around the world - Mexico, Turkey, Brazil, and South Africa. Each case examines what measures have been taken on China’s exports, how those actions fit into the broader economic and geopolitical context, and how Beijing has responded.

A regional survey of four Southeast Asian countries shows a tangled web of politics and economics

Southeast Asia has a unique mix of tense geopolitical issues involving China, notably in the South China Sea. Potential frictions also exist over its many developing regional value chains, and several countries have pushed back on some Chinese exports. Yet Beijing has shown no meaningful appetite to escalate economic disputes.

Southeast Asia has a direct impact on China’s security and geopolitical considerations. It presents Beijing with a web of bilateral and multilateral relations in a region it believes should be in its sphere of influence with a regional security order led by China, not external actors like the United States.

However, Southeast Asian countries are wary of aligning with China politically, unnerved by its expansionist actions, particularly in the South China Sea. China is a significant economic development partner, but Beijing’s regional ambitions pose potential threats to their national security. Vietnam is the most cautious. Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia engage more proactively with China’s economic offerings but are keen to avoid jeopardizing their neutrality, especially amid US-China competition. Large-scale Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) investments and infrastructure projects have built economic ties, but these do not necessarily translate into political support for China’s vision of an alternative world order. Adding to the complexity, Japan and Korea are both major geopolitical and economic partners, with historic baggage. China’s growing influence also recalls uncomfortable memories of its past tributary system, trade, and migration, even for some evoking the image of a new imperial power.

Furthermore, regional economic frameworks overlap in a patchwork fashion. The China-ASEAN free trade area (FTA) and other structures like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) are regionalizing local value chains for many diverse economies. A further complication is that the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) includes Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam, but not other members of ASEAN. Differences in alignment reflect each country’s historical ties, territorial concerns, and economic dependencies with China. While Thailand and Malaysia favor balanced policies due to strong trade ties with China, Vietnam and Indonesia prioritize sovereignty and security amidst regional tensions.

Vietnam looks for balance in a complex situation

Bilateral relations between China and Vietnam are complicated by Vietnam’s long history as a tributary state to China, a war in the early 1980s, territorial disputes in the South China Sea, and China’s dams on the upper Mekong River. While Hanoi has signed onto the BRI, it has not officially accepted any major BRI projects and is wary of Chinese involvement in its critical infrastructure.

China is Vietnam’s largest source of foreign direct investment (FDI) and trading partner, supplying nearly 40 percent of Vietnam’s imports and taking just over 20 percent of its total exports. Vietnam runs an overall trade surplus, but has a deficit with China of USD 45 billion.

It is therefore challenging for Hanoi to distance itself from Beijing. And yet, it has managed to impose trade defense measures across a wide range of product categories from China explicitly. Most are on commodities, basic manufactures, and e-commerce, and there is an ongoing investigation into wind tower products. Competition with Vietnamese producers is fierce, as some of Vietnam’s biggest export categories overlap with imports from China, namely electronics and machinery, vehicles and auto components, textiles, plastics, and agricultural products. Their firms therefore compete in third markets as well as in each other’s domestic markets.

Surging Chinese FDI and the prospect of integration into China’s value chains are huge opportunities. But Vietnam is also courting Japanese, Korean, Taiwanese, North American, and European investors eager for Vietnam to replicate China’s early boom years of high-speed growth. This helps Vietnam hedge against overreliance on China economically, even as it integrates quite heavily.

Vietnam’s "Bamboo Diplomacy" reflects a flexible, non-aligned strategic approach that conflicts with China’s ambitions to challenge the US-led order and assert a dominant regional influence. As a mid-sized power, Vietnam seeks to maximize its autonomy by carefully balancing relationships with both China and the United States. Yet, this positioning and the trade defense measures have not yielded a public pushback from China on the economic front.

Thailand continues its political and economic statecraft, playing foreign interests off of each other

Although Thailand is the oldest US treaty-ally in Asia (since the early Cold War) and has conducted joint military exercises more recently, Bangkok has little interest in strengthening its Western ties at the expense of its relationship with China. Thailand is rare in having no territorial or border disputes with China. Bilateral relations are stable and warm, supported by strong economic ties and China’s foreign information manipulation and United Front Work operations, which promote a narrative that the West is not reliable and China’s economic-political model should be Thailand’s path to follow. Thailand participates in several Chinese-led initiatives, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the BRI, though it does not fully endorse China’s global ambitions. Thai foreign policy favors “equal distance” in engagement with major powers. China’s new naval base in Cambodia has sparked concerns that the Gulf of Thailand could become an arena for US-China competition and endanger Thailand’s national security.

Thailand has raised significant barriers to Chinese exports of some commodities, mostly steel and aluminum oriented, and it has relatively high barriers on certain basic and advanced manufactures, which are overwhelmingly country agnostic. This is clearest in the automotive sector, where high tariffs on imported cars have long been the norm to encourage foreign automakers to invest in local production for domestic sale and regional export. Thailand’s automotive exports accounted for between 5-10 percent of GDP over the last decade. Thailand’s free trade agreements (FTAs) and involvement in RCEP and the CPTPP mean that the tariffs dissipate for auto exporters like China, Japan, South Korea, and to a lesser extent, India.

Thailand has only one major indigenous car brand, so is able play off foreign automakers to attract trade and investment. It has crafted unique deals with China to balance the trade and investment relationship. For instance, it allows Chinese EV firms access to Thai EV subsidies, on condition that EVs imported from China are matched by an equivalent number of locally produced vehicles by China’s brands (either for domestic sales or for export). However, even this opens the door to third market competition risks for both Thailand’s and established foreign automakers’ regional exports, as China’s EV makers are set on competing for ASEAN’s EV market through exports and localized production.

Malaysia juggles risks and opportunities, though more economic friction is likely

The relationship between Malaysia and China is relatively warm, despite conflicting claims in the South China Sea. Malaysia aims to elude friction, partly to avoid being seen as aligning with the Philippines against Beijing, given that Malaysia has its own sovereignty dispute with the Philippines over Sabah (or North Borneo).

Malaysia’s location on the Malacca Strait is of high importance to the BRI, with a troubled but central project being a railway across the Malay Peninsula. Malaysia is a major recipient of Chinese infrastructure projects within ASEAN, a member of the AIIB, and an applicant to join the BRICS. While Malaysia upholds strong economic ties with China, it has close security ties with the United States. It navigates major-power politics by remaining neutral and keeping equal distance from both China and the United States.

Malaysia has put limited trade defense measures on Chinese exports, mainly on steel and steel intensive products and some chemicals and polymers. Malaysia has its own strong metals industry and exports. It enjoys a trade surplus with China (around USD 15 billion), due to crude oil exports to China, which account for around 45 percent of its exports to China. Roughly one third of Malaysia’s total imports and exports are with China. However, China is still a minor and a relatively new investment player in Malaysia, even when combined with Hong Kong FDI data. China/Hong Kong FDI accounts for about 16 percent of total FDI stock (neighboring Singapore is the biggest FDI investor with 22 percent). But China’s role in Malaysia’s FDI is growing fast - in 2023, China/Hong Kong accounted for around USD 4.5 billion of FDI flows to Malaysia compared to Singapore’s USD 4.9 billion.

Malaysia’s current trade measures are a minor affair for Beijing which is keen to score political wins in the region. For now, their trade remains complementary, and FDI is a multiplayer game. However, as regional competition heats up, there are considerable overlaps in key basic and advanced manufactured goods that could create friction, both for Malaysia itself and for regional and third market competition.

Indonesia’s complementarity limits frictions, but China’s exports could stifle aspiring local businesses

In the Cold War, Indonesia’s anti-communist movement limited diplomatic activity with Beijing, but relations warmed in the 1990s and improved significantly after President Xi came to power. Indonesia has major Chinese BRI projects, such as the high-profile Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway. However, China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea, particularly its intrusion into Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone around Natuna Island, raises domestic concerns about compromising Indonesia’s sovereignty. In US-China competition, Indonesia is still haunted by its post-colonial struggles and Cold War memories, embedding a distrust of great powers. It attempts to balance its relationships with China and the United States by maintaining strong ties economic ties to Beijing and security ties to Washington.

As Indonesia's largest trading partner and second-largest source of investment, China plays a substantial role in Indonesia’s rapid economic growth. President Joko Widodo’s ambition is to transform the economy through massive infrastructure development, a perfect fit with the BRI. Indonesia lags far behind economic development in Thailand and Malaysia, barely matching Vietnam’s nascent economic miracle. The economy is still mainly centered around lower value production; its main exports are commodities and basic manufactures. Trade is complementary, built on exports of commodities like minerals and crude oil and imports of basic and advanced manufactures from China, plus FDI, which limits frictions. However, the value chain’s lower end has tensions. Indonesia is protecting nascent industries in chemicals, textiles, clothing and shoes, steel, and some antidumping and safeguard measures have been erected on imports from China specifically.

Yet again, Beijing’s public response is quite limited. Indonesia plays an important political role for China’s influence in ASEAN and the region, including by offering itself as an alternative to the US-led international system. Furthermore, Beijing is likely happy to tolerate trade defense measures in order to secure access to Indonesia’s minerals and energy exports, as well as to the country’s potential future export market and FDI destination.

Mexico leverages trade barriers to get Chinese investment, but mostly to deepen US links

China’s ties with Mexico are complicated by the latter’s close ties with the United States. Mexico’s status as a substantial regional power in the Americas means Beijing is keen to build strong bilateral ties for geopolitical reasons. Furthermore, many Chinese companies view manufacturing investment in Mexico as one way to circumvent US tariffs on their goods – for instance, by investing in factories for final assembly using components imported from China, so they can benefit from being inside the United States-Mexico-Canada-Agreement (USMCA) free trade bloc (formerly known as NAFTA).

Mexico is less warm with China than other countries in the region – it isn’t a signatory to the BRI nor a member of the AIIB. It is unhappy about the USD 62 billion trade deficit with China in 2023, as China takes only 3 percent of Mexico’s total global exports but supplies nearly 14 percent of its total imports.

Mexico has imposed China-specific measures on multiple goods, from steel to basic manufactures like zippers and screws, to hydraulic jacks and advanced goods like wind towers. In April 2024, Mexico also imposed tariffs on all imports of 544 different product types, exempting countries with a trade agreement. Those exempted include USMCA partners, the EU, other members of the 11-nation CPTPP partnership of Pacific Rim countries, but not China. This is driving more Chinese companies to consider investing in manufacturing in Mexico and nearshoring into the United States, though the recently-elected president Claudia Scheinbaum has threatened to restrict this process.

China’s response to Mexico’s tariffs has been extremely muted. If anything, Beijing is trying to warm up the relationship, in stark contrast to the kind of retaliation that the EU has experienced.

Turkey’s tariffs protect domestic industry while opening a gateway to the EU for China’s EV makers

Turkey occupies a peculiar position between the West and China. A NATO member, it was hostile to China during the Cold War, but has since distanced itself from the West and embraced China in some domains by joining the BRI. Yet, many irritants impede Beijing and Ankara’s efforts to deepen ties - Turkey’s perennial current account deficit, its USD 34 billion trade deficit with China (representing less than two percent of Turkey’s global exports but over ten percent of its total imports), and the impact on Turkish public opinion of China’s human rights abuses against the Turkic-speaking Uyghur minority.

Turkey has imposed wide ranging measures across all four product groupings: commodities like polyester fibers and hot rolled coil steel, basic manufactures like pacifiers and grinding balls, advanced manufactures like diesel engines and EVs, and e-commerce products valued below EUR 30. Industrial policy aims to see Turkey climb the value chain while shielding smaller industries that are key employers, so it has adopted many measures on trade distortions from China.

In June 2024, Turkey imposed tariffs on imported EVs from China at 40 percent or a minimum of EUR 7,000. Chinese EV companies exporting to Turkey must also invest in sales and servicing infrastructure. China has taken Turkey to the WTO, though results will take time. Meanwhile, BYD announced a USD 1 billion investment to produce EVs in Turkey, and other Chinese EV brands are reportedly considering similar action, to circumvent both Turkish tariffs on China-made EVs, and also the EU tariffs as Chinese EVs made in Turkey could dodge those measures because Turkey and the EU have an FTA.

That investment is small compared to FDI from the EU, but it still represents Turkey’s distinctive situation and ability to leverage its position vis-à-vis the EU market while advancing its own industrial policy and shielding its industry from China’s export surge. China’s decision to take Turkey to the WTO is exactly how it responded to the EU’s EV tariffs, but without any threatened investigations to identify goods for retaliation. The two countries may sell many overlapping exports to Europe, but the risk of Turkish goods sold to the EU being displaced by China’s exports presents a larger risk to Turkey’s total global exports than Turkey’s exports pose to China’s total exports. Meanwhile, China has little at stake in the Turkish market, so it has latitude to underreact economically in order to seek political progress.

Brazil weighs up its own industrialization, strong commodities sales and fears of dependence

Brazil-China relations have become warmer since left-winger and BRICS co-founder, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, returned to power in 2023 as he is more favorable towards China than his predecessor Jair Bolsonaro. Beijing is keen to enhance relations with Latin America’s largest country, which is a key source of commodities for China’s diversification strategy and a growing export market for Chinese goods. Lula's high-profile 2023 visit to China highlighted his vision of an "active nonalignment" strategy. His approach favors multi-polarity and prioritizes Brazil’s interests by emphasizing engagement with many international actors. China appears inclined to strengthen ties with Brazil now, especially since the 2024 election of right-wing President Javier Milei in Argentina has undermined its diplomatic efforts there. Nevertheless, Brazil is trying to balance between China and the United States and has yet to join the BRI, despite Beijing’s constant prompting.

The economic relationship presents Brazil with critical choices. It has received some Chinese greenfield FDI, specifically from EV firms producing commercial and passenger vehicles and batteries. However, the bulk of the economic relationship rests on Chinese commodities producers and traders. Huge increases in Brazilian commodities exports to China undermine Brazil’s industrial goals and desire to climb up the value chain. This is made harder by rapidly growing imports of Chinese goods in all four categories: commodities (like aluminum sheets and cold and hot rolled steel products); basic manufactured goods (like fiber optic cables and some medical devices which are currently under anti-dumping investigations); advanced manufactured goods (EVs and streetcars); and e-commerce. Many imports affected by Brazil’s measures are in categories where China is the primary or a major supplier.

Brazil is a rarity as it runs a trade surplus with China, pulling in a net gain of almost USD 65 billion. But this underscores its growing dependency, as China buys 36 percent of Brazil’s total exports and supplies 24 percent of total imports. Iron ore and crude oil are 40 percent of those exports; soybeans are 35 percent and meats 12 percent, leaving Brazil vulnerable to retaliation from Beijing. Brazil is a middle-income country where e-commerce is shredding many small retailers and cottage industries that provide vital low-skilled jobs, hence the tariffs.

Yet, Beijing has not openly leveraged Brazil’s increasing dependency in response to the country’s trade measures. This is likely due to a combination of China’s desire to establish itself as a leader of the BRICS nations and the Global South, and its strategic need to diversify key commodity sourcing.

South Africa sees China firstly as a political ally to amplify its voice

South Africa and China share a common interest in reshaping the Western-led global order and amplifying the voices of the Global South through such platforms as BRICS, the G20, and the African Union. For China, Pretoria is a valuable and capable partner in Africa and the Global South as it seeks to position itself as a world leader. South Africa, meanwhile, promotes the BRI and Beijing’s other international frameworks on development and security, and shares broadly aligned views on Ukraine and Gaza. South African foreign policy balances major powers and treats China as a counterweight to Western neglect and marginalization.

China is South Africa’s largest trading partner and has committed to investing in infrastructure, energy and advanced manufacturing capacity, particularly in green technology. China also pledges better market access for South African goods. South Africa is another rare country with a trade surplus with China, albeit a small one at USD 8.4 billion. Its exports to China are roughly 50 percent precious metals, around 30 percent crude oil and 10 percent iron and other metals. Like Brazil, South Africa is also highly dependent on China, which buys 29 percent of its global exports and provides 22 percent of its imports.

South Africa is also trying to climb the value chain and industrialize. State-owned enterprises control significant portions of the economy. South Africa has implemented trade defense measures on Chinese imports in all four categories: ongoing investigations into steel and iron products, anti-dumping measures on basic manufactures like safety glass and car tires, duties on e-commerce, and (comparatively low) country agnostic tariffs on advanced manufactures like automobiles (for which South Africa has many suppliers) and modest 10 percent tariffs on solar panels.

Beijing has not responded publicly to any of these measures. On the contrary, the readout from the two countries’ leaders’ recent bilateral meeting during this year’s Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in September expressed support for the development of South Africa’s manufacturing capacity and China’s willingness to receive greater volumes of finished goods from South Africa.

China likely views the political component of the relationship with South Africa as paramount and calculates its exporters can survive the hit. South Africa also provides China with some key commodities for its diversification efforts.

Beijing tolerates economic losses where it can make political advances, but swings hard against countries it has politically written off

Our survey has shown that the EU is far from alone in facing the need to respond to potential harms from a surge in Chinese exports that benefit from extensive hidden subsidies. However, from the Chinese party-state’s perspective, trade with many countries is viewed as a tool to achieve political goals. Beijing leverages its economic statecraft through massive state-led foreign investment schemes, such as the BRI, and its large domestic market for foreign imports. This enables China to use the market shares of Chinese goods in other countries in exchange for prioritizing political identity and alignment. Among the eight selected countries, all except Mexico and Brazil are signatories of the BRI. With the exception of Turkey, all are comprehensive strategic partners of China, and all except Mexico have joined the AIIB. Moreover, all but Vietnam have Huawei’s presence in their 5G networks. All these alignments indicate certain political foundations with China that justify China yielding on points of friction in the economic relationship.

When comparing China’s responses to trade restrictions, a clear trend emerges: Chinese policymakers prioritize political gains over economic interests where they see potential geopolitical wins. As a result, despite trade restrictions on Chinese goods from developing countries and the Global South, China has mostly refrained from retaliatory measures. In contrast, China’s response to countries that Beijing feels it cannot win over politically (or which have named China as a rival) is much sharper – such as the threats after the EU’s tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles were imposed, or previously in its trade war with the US and cases of economic coercion against Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Australia, Canada, and others.